- Home

- Mary Hooper

Holly Page 8

Holly Read online

Page 8

Ella just gave me a look and kicked the door shut without replying.

‘Don’t be like that!’ he said. ‘Tell us some naughties!’

Ella’s mum gave a little shriek of laughter.

They went out and Ella looked at me despairingly. ‘Oh, God,’ she said.

I nodded slowly. ‘Nightmare.’

‘I haven’t heard anything,’ she said dully.

I knew what she meant. ‘It’s too soon yet, isn’t it? They only wrote to him this week.’

‘Yeah, but if someone wrote to you saying you were their daughter, wouldn’t you just want to meet them straight away?’

I shrugged. ‘Dunno,’ I said. ‘Maybe I’d want to think about it first. Sort of come to terms with it.’

‘But he knew he had me!’ she said. ‘Not like you. Or him. That man – what’s his name?’

‘Ben,’ I said.

‘They would have written Wednesday, so he’d have got the letter on Thursday.’

‘But it’s only Saturday. And suppose he’s away on his holidays? It’s August, don’t forget. And suppose they’ve got the wrong one? Suppose it’s not him after all?’

She didn’t speak for a long time, then she said, ‘I hate it here. And I hate them.’

‘I know,’ I said.

It was my turn to pat her on the back.

We went out for a burger and saw Alex and a couple of his mates down the high street. I didn’t fancy talking much, though, or really doing anything, so we didn’t hang around. We went home and watched something mindless on TV instead.

At eleven the happy couple came back from the pub. Ella’s mum went into the kitchen and he stood in the doorway of the sitting room, holding on to the door handle and swaying.

‘Who wants a little nightcap?’ he kept saying. ‘Who wants a little nightcap with us? How about you, gorgeous Miss Holly Golightly?’

I decided to go home.

I didn’t really want to, but there was something inside me which made me crave for the normality of my home and my own bedroom with its lilac duvet and new roller blinds and nice pine furniture. And what was the alternative? There wasn’t one, apart from staying at Ella’s or running away.

When I got back Mum must have been standing behind the door, waiting, because she opened it as soon as my hand touched the front gate.

‘Have you been at Ella’s?’ she said. ‘I was just about to ring her. I do wish you wouldn’t walk home from there. Dad would have come and got you.’

I didn’t say anything, just lifted my eyebrows meaningfully at this last sentence.

‘I’m going to bed,’ I said, going past her and straight up the stairs.

‘We’re going to Nan’s tomorrow,’ Mum said. ‘You haven’t forgotten, have you?’

‘No,’ I said, clipped and cold. I carried on walking and didn’t even look at her.

‘Dad’s in the sitting room. Aren’t you going to say goodnight?’ she asked anxiously.

‘Night!’ I shouted and just carried on up.

I fell asleep quite quickly, but I woke after an hour and couldn’t get back again; I just kept going over everything in long and painful detail in my head. I felt removed and distanced from Mum and it was a horrible, scary and alien feeling. We’d rowed in the past, of course, but even when we’d had a real go at each other, I’d known that it was just a blip, a temporary, tiny thing that could never alter the basic structure of our relationship.

This wasn’t, though; this was a bomb, an earthquake, a destruction of the world as I’d known it. Everything I’d ever believed in was false.

I hated the man who’d done this, and I hated her as well. The only one I didn’t hate was Dad, downstairs. I loved him – but in the end, who was he to me? Not my dad, that was for sure.

Chapter Twelve

The next day I sat in silence in the back of the car, looking out of the window.

‘Nan’s making us one of her chicken pies,’ Mum said, glancing round at me. ‘Home-made pastry and everything.’

I grunted something.

‘I can’t remember the last time I made pastry,’ she went on brightly. ‘A dying art, pastry-making is. Soon no one will be able to do it. It’ll be like thatching.’

‘But people are still learning to thatch,’ Dad put in. ‘It’s one of those things that have started up again. People like houses with thatched roofs – it’s something to do with the nostalgia kick.’

‘I love thatched houses,’ Mum said. ‘And the more ratty the thatch, the better I like it. I think of all the little creatures who’ve made their homes inside it. Mice and birds and bats and … ’

Off she went again, pretending she cared about things. Pretending she was a nice person who loved her family and would never deceive them. I gave a loud sigh and Dad looked at me in the driving mirror. ‘What’s up with you, love?’

Mum glanced over at me anxiously. I saw a nerve twitch at the corner of her mouth.

I shook my head. ‘Nothing,’ I muttered.

‘Just a bit travel-sick, perhaps,’ Mum said.

I didn’t reply. How could this have happened to me? To my family? At school, I’d been one of the few to have an old-fashioned, quite boringly normal mum and dad, while others had single mums and dads or stepmums, dads, brothers and sisters coming out of their ears. I’d listened over the years, fascinated and appalled, to Ella’s and everyone else’s tales of stepparent horror, wondering how I’d managed to escape all these family ructions and even bizarrely wishing, sometimes, that I’d had some horror stories of my own to tell. I’d had no idea that I’d been living a horror story all along.

Now I knew that my family was just the same as everyone else’s. Worse, because at least people like Ella’s mum were honest, shedding husbands and boyfriends and picking up with new ones quite openly, whereas my mum was deceitful, lying, barbaric, even – passing off another man’s child on her husband without a qualm.

On the surface everything was the same. Underneath, though, the whole structure of my life had collapsed. I felt as if I had no control over my destiny any more; that anything could happen. Suppose he – Ben – put in a formal claim for me and took me away and made me live in America? I’d heard about tug-of-love babies and children – could you do that with teenagers?

What was going to happen? Was I going to tell anyone? What was I going to do?

‘You’ve hardly touched your pie!’ Nan said reproachfully. ‘I thought it was your favourite.’

‘It is,’ I said guiltily. ‘I’m just not very hungry.’

‘I got up early to catch that chicken, too,’ Grandad said, and I tried to smile.

We were sitting round the red Formica table in the kitchen of Nan and Grandad’s bungalow. All around were the things I remembered from way back in my childhood: the green plastic clock with the broken hand, the teddy-with-shield ornament I’d bought when I was three saying, ‘Best Nan in the world’, the postcards round the mirror, the plastic sheet with ‘Everyday Phone Numbers’ written on it, the dusty jug with an assortment of pens that didn’t work.

‘I hope you’re not going on one of those silly slimming kicks,’ Dad said. ‘I can’t bear those women who look like stick insects.’

‘No, of course she wouldn’t!’ Mum said, ever-bright, ever-cheerful. ‘Holly’s much too sensible for that.’

‘Are you looking forward to getting back to school?’ Grandad asked.

I shook my head, pushing a sprout around my plate. ‘I’ve quite enjoyed the freedom, actually. And I like having money to spend.’

‘That job at the tea shop’s been really good for you,’ Nan said. ‘I expect you’ll work there every summer now, won’t you?’

‘Probably,’ I agreed.

‘Just tourists you get in there, is it?’ Grandad asked.

I nodded. ‘Mostly.’

‘Tourists and your secret admirer!’ Dad chipped in.

Opposite me, Mum dropped her fork on the floor.

‘W

ho’s that, then?’ Nan asked.

‘Someone’s been sending our Holly presents,’ Dad said. ‘Scarf and flowers and something else – ’

‘Earrings,’ I said.

‘Well, I never!’ Nan said. ‘Were they nice?’

I nodded.

‘How exciting! And you’ve no idea who they’re from?’

It was a long while before I shook my head. Long enough for Mum to turn pale.

Later, me, Mum and Nan were sitting on the back porch watching Dad and Grandad cutting the hedge at the side of the garden.

I was looking at Dad and thinking it was just impossible to think he wasn’t Dad when it suddenly struck me. If he wasn’t Dad, then these two, his parents, weren’t Nan and Grandad. They were total strangers. I didn’t know why I hadn’t thought of it before. And then, of course, Dad’s brother and sister weren’t my auntie and uncle, and my cousins weren’t my cousins, and that new baby my cousin Sammy had just had, which everyone said was the spitting image of me, wasn’t actually the slightest bit related.

I didn’t have any relations except Mum. And I didn’t want her.

‘Your dad’s putting on weight,’ Nan said as we sat there.

‘Who?’ I said. I knew it wasn’t really fair of me to bring this nice old lady who wasn’t any relation of mine into it, but I was trying to get back at Mum and make her feel uneasy.

‘Your dad,’ Nan said, all unaware. ‘He’ll have to cut down on his portions of bread pudding. Still his favourite, is it?’

‘Yes, he loves it,’ Mum said. Her voice sounded tight and strained.

Nan went inside to make tea and while she was out of the way, Mum said something about it being hot. I didn’t answer. How could she have an affair with anyone? How could she deceive Dad? I moved my chair so that it was slightly facing away from her. I hated her!

‘I don’t know what’s the matter with you two today,’ Nan said suddenly, coming out with a full tray of tea things. ‘Not your usually bright and bubbly selves, are you?’

‘Aren’t we?’ Mum said. ‘Must be the weather. I was just saying to Holly that I keep coming over in big waves of heat.’

‘Ah! Hot flushes,’ Nan said, putting out cups. ‘I remember them well.’

‘I suppose that’s what it is,’ Mum said.

Was I going to tell anyone? What would happen if I told Dad?

Nan suddenly started laughing. ‘You’ll never guess what I’ve done,’ she said. ‘Put the hot water in this jug and – well, I don’t use it very often. See for yourself.’

And she tipped up the jug to show us a small roll of banknotes floating in the hot water. ‘It’s my secret savings!’ she said. ‘I stash a little bit of money away every week out of the housekeeping – keep it in the jug.’

‘What d’you keep it there for?’ I asked.

Nan put her finger to her lips. ‘Sssh. I like to have a little secret hoard,’ she said. ‘I put it in there so your Grandad won’t find it.’

I knew she was only messing around and it wasn’t serious, but I suddenly felt sick. Everyone had secrets from each other. No one was exactly as they seemed, and therefore the whole world was based on lies!

My eyes filled with tears. Abruptly, I got up and ran down to the bottom of the garden, past Dad and Grandad.

‘Oh, dear,’ I heard Nan say. ‘What’s up with our Holly?’

‘Just her hormones, I expect,’ Mum said.

Chapter Thirteen

‘Your hat’s drooping,’ Ella said, reaching up to try and adjust the silly bit of white material on top of my head.

‘Never mind that,’ I said. ‘I’m drooping.’

It was coffee break and I’d just come down to the staffroom. We had five minutes together before Ella had to go back to serve in the shop.

‘What happened yesterday, then?’ she asked.

‘Nothing. Went to Nan and Grandad’s,’ I said. ‘Or should I say, went to Mr and Mrs Devine’s. They’re the parents of the man I live with. My mum’s husband.’

Ella grinned at me. ‘At least you’ve got them and they’re nice.’ She stood up and rustled her long skirt. ‘If I find my dad, I might find I’ve got a nice nan and grandad too.’ She started up the stairs. ‘Talk to you properly at lunchtime,’ she said.

I slumped, nibbling round the jam doughnut I’d bought downstairs. What was I going to do? How could I just go on at home pretending things were the same? What was going to happen?

At two o’clock that morning I’d woken up frightened – terrified – and for a while I hadn’t been able to think why I was, just known that there was a knot of terror in the pit of my stomach. Then I’d remembered why it was there, and I’d twisted and turned and lain in a hundred different positions to try and soothe it away, but in the end I’d had to go downstairs and get a hot-water bottle. Once I had that, I’d screwed myself up into a foetal position, bottle on my tummy, and tried to rock myself to sleep. Talk about pathetic – I only just managed to stop myself from sucking my thumb.

It had been ages before I’d been able to get off again: I’d watched the silvery laser arms of my bedside clock gently touch all the way round the clock face at least three times. Mum was awake, too, and I was nastily pleased about that. I heard her go into the bathroom a couple of times and then, around four, go down to the kitchen and make a cup of tea. At any other time, if I’d heard her down there in the night, I would have gone to see if she was all right and we might have shared a cuppa and a biscuit – but not now. All that was finished.

It was Mrs Potter’s day off so we weren’t too rushed that morning. We had as many customers, but we just didn’t bother quite as much with them – like, we didn’t rush up the moment they arrived to greet them, or clear the tables quite as readily. Cody tried to keep us up to scratch, but we didn’t work the same for him.

At lunchtime Ella rang the helpline again.

‘They said they’d ring you if they heard anything,’ I reminded her as she dialled.

‘They’re busy people,’ she said. ‘They might not have had time. I’ll just save them the phone call.’

She got through to Maureen and I saw her face drop. ‘Nothing? Nothing at all? Why d’you think that is?’

Ella beckoned me to come nearer and I squashed myself by the phone. ‘The person at the garage could be away – or maybe he just hasn’t bothered to respond,’ I heard Maureen say.

‘Could you tell me where the garage is?’ Ella asked. She put her hand over the mouthpiece. ‘We could go there,’ she mouthed to me.

‘I’m afraid we can’t tell you that. You see, some people want to stay missing and we have to respect their wishes.’

‘D’you think he wants to stay missing?’ Ella asked anxiously.

‘It’s too soon to say,’ Maureen said. ‘And don’t forget, we might not even have the right man. The only information we’ve had is a call from someone saying that a man of the same name works at his garage.’

‘Suppose it’s not him, then? What happens next?’

‘We’ll just carry on looking. There are other things we can try – other places we can look for him. Try not to worry.’

Ella said thanks and sorry to have troubled her and then put the phone down and stared at me. ‘They’ve got the right bloke – bet it is him in the garage,’ she said. ‘I’ve just got a feeling about it.’

I didn’t know what to say.

‘It’s him but he’s got another family now and he just couldn’t care less about me.’

‘Don’t be daft! Why have you suddenly started thinking that? You’ve been listening to the pillock, haven’t you?’

She shook her head. ‘It’s just common sense. I’ve got to face it. He would have found some way to get in touch if he wanted to. If he really cared about me.’

I shrugged. ‘Maybe he’s somewhere abroad – ’

‘Oh, yeah. Abroad somewhere you can’t send letters from. Like, he’s in the middle of the jungle or something and he’s been there f

or fourteen years and never seen a post office.’

As I grinned, she added, ‘I’m beginning to wish I hadn’t started looking.’

‘How’s that?’

‘Well, all the time I wasn’t looking for him I could pretend how it would be if I ever found him. But if I do actually find him and he doesn’t want me, then that’s much worse … ’

I made sympathetic noises. I didn’t know what else I could do.

Cody shouted down to us that we were three minutes late getting back from lunch and what did we think this was, a place of work or a rest home, so we went up and I took over from Mandy on section three.

The first customer I saw was him, Ben, sitting there with his long legs stretched out into the aisle and an Earl Grey tea in front of him.

My legs automatically went into wobble mode and I turned to go back downstairs. Cody was standing at the top of them barring my way, though, so there was nothing for it but to walk up to his table and face him.

‘What are you doing here?’ I asked coldly.

He gave a small smile, spread his hands. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘Couldn’t resist it. I go back to the States on Wednesday morning so this is my last time. Positively my last visit. After Thursday you can relax.’

‘Why did you come?’ I asked. ‘I wish you hadn’t.’

‘Sorry,’ he said again. ‘I know you do.’

‘You’ve made my life … ’ I shrugged; hell didn’t seem strong enough. There wasn’t a word to say how much he’d wrecked things. ‘My life was quite OK before – the only thing I had to worry about was whether my jeans were the right make. Now it’s a mess.’

‘I can only imagine,’ he said. ‘And for that I’m profoundly sorry. Look, can you just sit down with me for ten minutes – ’

‘No!’

‘Five minutes, then? Two minutes? Two minutes is all I ask. I just want to talk to you. Tell you how it was between your mom and me.’

I glanced towards Cody. ‘I don’t want to hear things like that.’

‘I think it would help. I’d just like to clear a few things up before I go back. I don’t want to go off leaving your life in complete chaos. I’d feel better if you were straight on just a couple of things. Please. If you could bear it.’

At the Sign of the Sugared Plum

At the Sign of the Sugared Plum Zara

Zara Megan 3

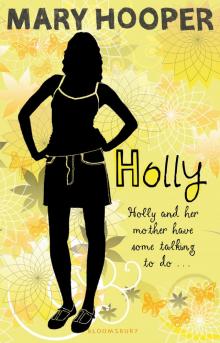

Megan 3 Holly

Holly By Royal Command

By Royal Command Newes from the Dead

Newes from the Dead Amy

Amy Poppy in the Field

Poppy in the Field Poppy

Poppy Velvet

Velvet At the House of the Magician

At the House of the Magician The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose

The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose Chelsea and Astra

Chelsea and Astra The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Disgrace of Kitty Grey

The Disgrace of Kitty Grey Fallen Grace

Fallen Grace