- Home

- Mary Hooper

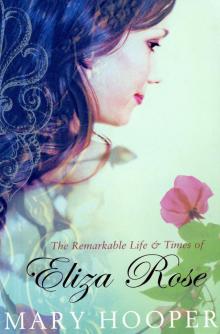

The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose

The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose Read online

The Remarkable Life & Times of

Eliza Rose

MARY HOOPER

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty One

Chapter Twenty Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty Six

Chapter Twenty Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Epilogue

Cast of Characters

Places Featured

Also by Mary Hooper

Back ads

Prologue

Somersetshire, 1655

The castle bedroom is large and richly furnished. Paintings and costly tapestries line the panelled walls and in the centre is a vast four-poster bed hung about with heavy drapes. Childbirth being a close and private matter, no outside light is allowed to penetrate the room, so the window shutters are secured tightly and heavy damask curtains hang across them. Light is provided by the fire burning in the grate and several silver candlesticks holding tall wax candles. A large white china bowl of lavender and rose petal potpourri standing on a table diffuses a faint fragrance.

There is a tap on the door and a woman within opens it. Notwithstanding her years, she is both handsome and elegant. A maid carrying a copper scuttle, full of coal, makes as if to enter. She is stopped by the woman, who takes the scuttle from her.

‘Please, madam, it’s very heavy,’ the maid says. ‘And you’ll get all covered in smuts.’

‘That’s of no account,’ the woman says. ‘I don’t want my daughter disturbed.’

The maid glances at a younger woman lying on the bed. ‘How does she?’

‘She progresses well.’ The older woman goes to shut the door.

‘Are you sure that I can’t get the midwife for you? Or the housekeeper or the doctor?’

‘No one, thank you,’ the woman says firmly, and, the maid not going away, has to shut the door in her face.

‘Who was that?’ the younger woman calls.

‘Hush! No one – just the maid with some coals.’

‘Did she –’

‘Hush!’ the older woman says again. ‘She didn’t see or say anything.’ She puts some coal on to the fire and then wipes her hands and goes over to the bed where the woman lying on the linen oversheet is in the final stages of labour. She waits while another pain ebbs and flows through the woman’s body and then, when there comes a moment of calm, helps her sit up on the bed and places pillows behind her. Then she holds a cup to her lips.

‘What is it?’

‘A herbal drink: tansy and juniper. I had it prepared by my own apothecary. ’Twill help and give you strength for the final ordeal.’

The other groans. She looks towards one of the tapestries on the far wall. ‘Is the babe still there?’ she whispers.

‘You know he is. He’s arrived and is quite safe.’

‘Suppose he cries?’

‘Then there’s only you and I to hear him.’ She dabs a cloth to the other woman’s temple.

‘Are Kathryn and Maria well?’

‘Kathryn and Maria are very well and happy. They are with their nurses. Now, concentrate on this coming child and –’

A mighty pain seizes the other woman and she throws herself back on to the pillows, turning to bury her face among them to stop herself from screaming.

‘Soon, now. Soon,’ murmurs the older woman when the pain passes. ‘It can’t be much longer.’

‘You’ve been saying that for hours!’

There are heavy footsteps outside, then the door opens and a man calls from the doorway. ‘Is he here, then? Is my son in the world?’

‘Not yet,’ the older woman says, and she and the woman in bed exchange anxious glances.

The man strides into the room. He has a large nose, puffy eyes and is weak of forehead and chin. He’s been hunting and his hands are stained with the blood of small creatures.

‘What, still not arrived?’

‘Soon,’ the woman on the bed says weakly. ‘Very soon.’

‘But where’s the midwife? Where are the goodwives and neighbours to attend the birth?’

‘My daughter wants complete quiet this time,’ came the reply. ‘She has asked – nay, insisted – that I should be the only one attending the birth.’ She tries to smile at the man. ‘’Tis all feasting and gossip when the neighbours come in and ’tis difficult to get any rest.’

‘That is the custom, though,’ the man says, but then he shrugs. He puffs out his chest. ‘My son!’ he says. ‘I’ve long waited for this.’ He looks from one woman to the other carefully. ‘And you’re quite sure that it will be a boy this time?’

‘Very sure, my lord,’ the older woman says with confidence. ‘The hour the child was conceived and the potions my daughter was taking have ensured that your next child will be male. Besides, we have consulted various wise women throughout her time.’

‘Quite so,’ said the man. ‘Because if –’

‘Please!’ The older woman holds up her hand. ‘Please don’t alarm my daughter at this time with your threats and intimidation. I can assure you, sire, that the coming child will be a boy. I’m perfectly sure of it. There will be no need for my daughter to be turned out of doors.’ She looks at the man coldly as she speaks, for there’s no love lost between the two of them, and then the woman on the bed lets out a sudden, piercing scream. The man hastily leaves the room, asking to be informed the moment the birth has taken place.

As his footsteps retreat the younger woman says, ‘I screamed so that he’d go!’

Her mother nods, smiling. ‘It was well-timed.’

‘I was scared that there would be some noise from the passageway.’

‘Hush!’ the reply comes. ‘Just forget the babe’s there. All will be well.’

An hour goes by and the pains begin to come one after the other without a gap between. The older woman, knowing it is almost time, goes to the bedroom door and bolts it. Then she climbs on the bed to help her daughter, rubbing her back and murmuring endearments and encouraging words.

At last, with one final push, one tremendous effort, the child is born. Even before the cord has been cut the younger woman is struggling to sit up and look down at the baby.

‘What is it?’ she asks frantically. ‘Is it a boy?’

Her mother shakes her head and sighs. ‘No. Another girl.’

‘Let me see …’

‘’Tis better if you don’t.’

‘Is there anything wrong with her?’

‘Not a thing. She’s a healthy size and all complete.’

The older woman swiftly cuts the cord, then wraps the child in a linen cloth, swaddling her round and round.

‘Let me …’ the new mother says, and the other relents and holds the tiny bundle towards her. ‘So much like Maria!’ she murmurs, taking the child.

‘Quickly!’ the other says.

‘Poor little child,’ says the young woman. �

�Will your new mamma love you as I do? Will she tell you fairy tales?’ She looks down at her daughter for the first and last time. ‘Once upon a time,’ she whispers, ‘there was a beautiful child born in a castle …’

Chapter One

London, fifteen years later

‘Come along, my pretty one. Just you come by here …’

The voice woke Eliza but was unknown to her. It was close by, but she lay still, wanting to feign sleep until she was quite sure of where she was.

‘That’s it, my beauty. Go into the box …’

Perhaps it wasn’t she, then, who was being addressed? But still, best not to risk opening her eyes and being noticed. She tried to gauge what was happening without stirring herself. Where was she, for a start? Not at home, that much was sure. Home had never been this cold. Nor, she realised as her senses slowly returned, had it ever stunk quite so badly.

Eliza moved her foot slightly to try and judge on what sort of surface she was lying and felt a sort of slimy, gritty dampness beneath her. She was on the ground somewhere, then, without covering, and if her head hadn’t been cushioned by her arm then her face would have been down in the slime too.

There was a sharp, sudden noise, like a box being banged shut. ‘Got you, my beauty!’ said the same female voice, with a cackle of laughter. There was then some crooning and whispering – it was ‘Beauty’ who was being addressed, Eliza supposed.

She now felt it safe to open her eyes. When she did so, however, the view before her was so disturbing that she immediately shut them again. In that instant she’d seen a long, low-ceilinged space, poorly lit by tallow candles, and some bedraggled and filthy creatures sitting around its walls, all of whom looked to be in a state of utter despair and dejection.

So, she wasn’t at home – but nor was she anywhere she could ever remember being before.

So what could she remember? Dimly, the recent past came back to her: leaving her home in Somersetshire, begging lifts on carts and haywains and, once, a river craft and then, days and days later, arriving in London and quickly getting lost in its dark byways. And becoming cold and scared and hungry.

And then … stealing a hot mutton pasty from the pieman.

There was the answer to where she was.

Eliza’s eyelids flickered open again. To the left, not many inches from where she was lying, was a shallow channel which had been dug out from the hardened earth. There were neither windows nor ventilation in the room, and the stench from the channel – which was no more than an open sewer conveying filth and human waste, she realised – hung chokingly on the air of the room. Which wasn’t a room at all, but a cell.

She was in prison.

Slowly, she sat up and, shuffling backwards and away from the stinking ditch, leaned against the wall. Then she surveyed her fellow prisoners.

There were perhaps twelve in the room. All were women, and four of these looked to be chained with heavy iron fetters hard against the wall. Others sat on wooden pallets or lay on the floor, curled up – whether alive or dead Eliza didn’t know. The woman whom Eliza had heard a moment before was sitting nearby, crooning softly to a brown rat in a rough wood and wire cage.

‘My pet … my sweetheart,’ she was saying, ‘I’ll feed you and make you fat.’

Eliza shivered and instinctively crossed her arms around herself in an attempt to get warm. She seemed to have lost her bundle of possessions, her woollen shawl and her cap and shoes along with them. At least, she thought, they hadn’t been able to take any money from her, because the small amount she’d possessed had already been spent on the journey to London.

Her stomach ached with hunger. She thought about the pasty she’d stolen. Where was it? How long ago had she stolen it? A vision of it came into her head: warm, crumbling pastry outside and mutton and spiced potato within. Had she actually eaten it?

She feared that she had not, for she remembered now that she’d taken it from the counter of an open shop in Leadenhall and carried it swiftly around a corner to eat. She’d lifted it to her lips, opened her mouth to take a bite – actually felt it crumble on her lips – and then the shopkeeper had raced up, red-faced, apron flapping, and, calling for the watchman, had knocked her to the ground. ‘Varmint! Thief!’ he’d yelled. ‘Taking food from honest ’keepers! I’ve seen your like here before.’

And then she could dimly remember being dragged through the streets and, though she couldn’t remember as much, must have been thrown into this prison cell. She felt in her pocket, without much hope. If only she’d thought to shove the pasty – even half the pasty – into her pocket for later, then at least she wouldn’t die of starvation. Which, right at that moment, she felt was a possibility.

Her eyes fell on the large brown rat who was running first to one corner of his cage then the other, scrabbling, frantic to get out.

‘You won’t get out of there, my pretty darling,’ the old woman said. ‘You won’t get out yet-a-while.’ Her eyes slid past the rat to Eliza. ‘So you’re awake now, are you?’ She moved the box containing the rat so that it was out of Eliza’s view. ‘Don’t you set your eyes on him!’

‘I wasn’t,’ Eliza said. Her voice sounded hoarse, croaky. How long was it since she’d spoken?

‘Because he’s my rat,’ the old woman said. ‘My own pretty rat.’

The woman seemed to be little more than a bag of bones and a handful of rags, but Eliza thought it best to humour her. She asked, ‘Is he your pet?’

‘No, he’s not my pet, dearie,’ the woman said, and her sunken cheeks creased and formed into a gummy smile. ‘He’s my dinner! He’s my dinner as soon as ever he’s good and ready. I’ll feed him all sorts of pieces and soon get him plump.’

Eliza felt her stomach lurch and she shuddered with revulsion.

‘You needn’t look so dainty,’ the woman said. ‘After two months in here you’ll be happy to eat your own arm.’

‘Where … where is this place?’

‘Where? Why, this is Clink Prison in Southwarke,’ the woman said. ‘’Tis famous. Haven’t you stayed here before?’

Eliza shook her head. ‘I’ve not long been in London.’

‘And so soon acquainted with its worthy buildings!’

‘I was hungry,’ Eliza said. ‘I stole a pasty.’

‘And I stole a whopping big pearl from a shop in Cornhill,’ the woman returned, and cackled with laughter. ‘A pasty or a pearl – see, we’re all equal here.’

Locked up with a jewel thief, Eliza thought. How her stepmother would have laughed.

‘’Tis not so bad in here,’ the woman said. ‘Look about you.’ She pointed at the stone walls which were trickling with brackish water. ‘See the water laid on, just like in the big houses.’ She extended her arm to include the mould and fungi growing from fissures in the stones, which had formed themselves into irregular shapes and colours. ‘And the paintings and tapestries all provided for our delight!’ Eliza did not reply, thinking the woman at least half-mad, and she went on, ‘And here are your new friends and neighbours.’ She pointed to the hunched, shabby figures crouched or lying against the far wall. ‘A pretty and an elegant lot! Some in lace, some in ermine. See their jewels sparkling! Why, you might think yourself in the court of the king when you’re in Clink Prison!’

Eliza regarded her wordlessly. She had a dull ache in her head and, putting a hand up to her face, felt a bump on her forehead. Her legs and arms were stiff and aching too, as if she’d been lying in the same position for some time.

‘How long have I been here?’ she asked. ‘Can you tell me?’

The woman shrugged. ‘A day and a night. Two days, maybe. They threw you in like a sack of potatoes and there you stayed.’

Eliza tried to work out what the date might be. She’d left Somerset on a Monday during the latter half of April, had walked for about seven days, had two days travelling in hay carts, then walked again a good while. She’d managed to journey two days on a river barge and used up her last

coins by entering London in some style on top of a post-coach. She’d then spent a day or so wandering about the city, stunned and exhausted by the crowds and the noise and the goings-on.

‘Is it May?’ she asked. ‘And is today Sunday?’

‘Not Sunday,’ the woman said. ‘We get meat of a Sunday. And you hears church bells then. But ’tis monstrous difficult to tell one day from the next and one month from another, for ’tis all the same in here.’

Suddenly becoming aware of some shouting from outside, Eliza bent her head to one side to listen better, causing a waterfall of dark hair to fall around her shoulders.

The woman put out her hand to touch it, and it was such a skeletal, wizened hand that Eliza couldn’t help but draw back. ‘Ah, don’t mind old Charity,’ the woman said. ‘Lovely hair you’ve got, dearie. Black and shiny as oil. You could sell that.’ She dropped her voice. ‘And for a fact, you owe Charity here a favour. They would have cut your hair off while you were asleep, but I stopped them.’

‘They were going to cut it off?’ Eliza said in alarm, and, throwing back her head, wound her hair into a knot and tried to tuck it up. As she had no cap nor pins, however, it tumbled down again.

‘Five silver shillings, that would fetch,’ Charity said. ‘Maybe more.’

‘I’m not selling it!’ Eliza said. She wondered if she’d been too sharp with the woman and added, ‘But thank you kindly for saving it for me.’ The same shouts and screams came from outside again and Eliza asked Charity what it was.

‘Why, that’s just the rest of our friends and neighbours!’ she cawed, and Eliza looked away quickly from her gaping, toothless mouth. ‘They’re a-parading themselves in the yard right now, but they’ll be in soon and you can meet ’em. What a grand lot they are, too!’

Eliza nodded towards the others in the cell. ‘Why isn’t everyone outside in the yard? Isn’t it better than being stuck in here?’

‘Oh, I don’t care much for outside myself,’ Charity said. ‘And I had my pretty meal to catch. As for them over there … they’re all as lazy as hogs in mud.’

‘Or too ill to move,’ Eliza said, as a long sigh caused her to look over to the hunched and bedraggled figures once more. ‘How long have you been here?’ she asked.

At the Sign of the Sugared Plum

At the Sign of the Sugared Plum Zara

Zara Megan 3

Megan 3 Holly

Holly By Royal Command

By Royal Command Newes from the Dead

Newes from the Dead Amy

Amy Poppy in the Field

Poppy in the Field Poppy

Poppy Velvet

Velvet At the House of the Magician

At the House of the Magician The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose

The Remarkable Life and Times of Eliza Rose Chelsea and Astra

Chelsea and Astra The Betrayal

The Betrayal The Disgrace of Kitty Grey

The Disgrace of Kitty Grey Fallen Grace

Fallen Grace